|

Here are some example solutions to the activities from Tutorial 1.

TriangleTestJ4.java with more tests added. Notice that the answer sheet from the

Lecture 1 quiz suggested trying all permutations of the test inputs

(so don't just test that (4, 5, 6) is scalene, test also that (4, 6, 5),

(5, 4, 6), (5, 6, 4), (6, 4, 5) and (6, 5, 4) are scalene), so I've

implemented a new method called permutedScaleneTest() which

tests that all six permutations give the right answer. I also

implemented a method called scaleneTest() which runs a

single test for a triangle, but prepends that triangle's details to the

message that's printed if the test fails:

TriangleTestJ4.java: testing lots of Triangles: |

|---|

package st;

import static org.junit.Assert.*;

import org.junit.Test;

public class TriangleTestJ4 {

@Test

public void testTriangle() {

fail("Not yet implemented");

}

// This constructs a triangle and makes the appropriate assertion

// (either it is scalene, or it isn't scalene). It's used by

// permutedScaleneTest in order to test all permutations of a

// particular triangle together. It prefixes the triangle's dimensions

// to the error message m.

private void scaleneTest(int p, int q, int r, boolean scalene, String m) {

Triangle t = new Triangle(p, q, r);

m = "(" + p + ", " + q + ", " + r + ") " + m;

assertEquals(m, t.isScalene(), scalene);

}

// This tests that all permutations of a triangle give the right answer

// to isScalene(). m is used as an error message if a test fails.

private void permutedScaleneTest(int p, int q, int r, boolean scalene, String m) {

scaleneTest(p, q, r, scalene, m);

scaleneTest(p, r, q, scalene, m);

scaleneTest(q, p, r, scalene, m);

scaleneTest(q, r, p, scalene, m);

scaleneTest(r, p, q, scalene, m);

scaleneTest(r, q, p, scalene, m);

}

// Most of these tests are inspired by the Tutorial 1 quiz answer sheet.

@Test

public void testIsScalene() {

permutedScaleneTest(4, 5, 6, true, "should be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(4, 3, 2, true, "should be scalene!");

// No permutations needed for this one...

scaleneTest(9, 9, 9, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(4, 4, 2, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(0, 4, 2, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(0, 0, 2, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

scaleneTest(0, 0, 0, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(-5, 4, 2, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(-5, -1, 2, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(-1, -2, -3, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(1, 2, 3, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(1, 1, 9, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

}

@Test

public void testIsEquilateral() {

Triangle t = new Triangle(4, 5, 6); // Not equilateral

assertFalse("(4, 5, 6) unexpectedly equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

t = new Triangle(1, 1, 1); // Equilateral

assertTrue("(1, 1, 1) unexpectedly not equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

t = new Triangle(0, 0, 0); // Not a triangle

assertFalse("(0, 0, 0) unexpectedly equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

}

}

|

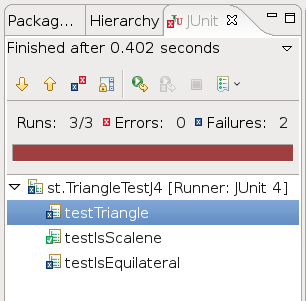

Also notice that there's a bit of a problem here:

testIsScalene() fails on the tests for triangle (4, 4, 2).

An exception is thrown at this point, so none of the

testIsScalene()tests after the (4, 4, 2) test are

executed. That's a risk when bundling a lot of tests up into one

method like this. So long as you expect all of the tests to pass, and

fix things as soon as one of the tests fails, this isn't too much of a

problem. Otherwise failures will prevent other tests from running, so

if you do expect quite a few failures and aren't going to fix them

quickly, you should only have one test per method.

Triangle.toString() method: Here

are the modifications you could make to add a toString()

method to Triangle.java. Note the addition of the

description field so we remember the order of the side

lengths that the user called the constructor with (otherwise, since we

re-order the sides so that the longest one is stored in p,

we wouldn't be able to differentiate between Triangle(4, 5,

6) and Triangle(4, 6, 5) for example).

Triangle.java: toString() method. |

|---|

…

private int r;

private String description;

public String toString() {

return description;

}

public Triangle(int s1, int s2, int s3) {

description = "Triangle (" + s1 + ", " + s2 + ", " + s3 + ")";

// Ensure that p is the largest of the three.

if(s1 > s2) {

…

|

Once we've made the above changes to Triangle.java, we

can tidy up TriangleTestJ4.java a little:

TriangleTestJ4.java: after writing Triangle.toString(). |

|---|

…

private void scaleneTest(int p, int q, int r, boolean scalene, String m) {

Triangle t = new Triangle(p, q, r);

m = t + " " + m;

assertEquals(m, t.isScalene(), scalene);

}

…

@Test

public void testIsEquilateral() {

Triangle t = new Triangle(4, 5, 6); // Not equilateral

assertFalse(t + " unexpectedly equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

t = new Triangle(1, 1, 1); // Equilateral

assertTrue(t + " unexpectedly not equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

t = new Triangle(0, 0, 0); // Not a triangle

assertFalse(t + " unexpectedly equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

}

…

|

Notice how we can now just add t to any string we

construct (in the messages for the assert calls, in

particular) and it'll automatically get converted to a nice text form

using the new toString() method.

isScalene() implementation you have makes six

tests against p, q and r:

p > 0 && q > 0 && r > 0 && p < q + r && (q < r || q > r)

The first three tests are just to check that all of the sides have a

positive length. The fourth one, p < q + r, checks that

the sides can make a triangle: translate it into words, remembering that

p is chosen to be the longest side by the

Triangle constructor, and it says “the length of the

longest side is less than the sum of the lengths of the other two

sides” — if this wasn't true, then the two short edges

wouldn't between them be able to reach from one end of the long edge to

the other, so they couldn't possibly make a triangle! So the first four

tests are really just about making sure that p,

q and r can make a triangle at all.

The fifth and sixth tests then should be the ones that

really test to see if we've got a scalene triangle. But what

are they doing? Checking to see that q < r or q

> r? That only ensures that the two shorter edges have

different lengths, but makes no such statement about their relationship

with the long edge. So this is the error. We need to replace them with

a test to see that p, q and r are

all different — for example:

(p != q && p != r && q != r)

After this change, at last our scalene tests pass:

Triangle constructor throw an exception if it's given

an invalid set of parameters. First we need to write the exception

class; it's pretty straightforward:

BadTriangleException.java |

|---|

package st;

public class BadTriangleException extends RuntimeException {

public BadTriangleException(String m) {

super(m);

}

}

|

The constructor allows us to add an explanatory message when we throw

this exception. Note that BadTriangleException inherits

from RuntimeException, which means that you don't need to

add any throws clauses for it. Unchecked

exceptions are a cause of much debate though, so don't do this

without understanding the argument. Page 6 of Lecture 2's slides breaks the

different exception trees down a bit, but the above page on Sun's site

is an important read.

(Aside: the eagle-eyed among you might notice a warning from Eclipse: “The serializable class BadTriangleException does not declare a static final serialVersionUID field of type long.” If you want you can autocorrect it (“Add generated serial version ID”); this page on Java serialization will tell you more…)

Now that we detect bad triangles in Triangle's

constructor, isScalene() doesn't need its first four

conditions (which check that the triangle is valid), and many of our

tests in testIsScalene and testIsEquilateral

have become redundant — these should now be moved to

testTriangle, which tests the constructor (more on that

later). Here are the new versions of all three methods:

New version of Triangle.isScalene() |

|---|

public boolean isScalene() {

return p != q && p != r && q != r;

}

|

New versions of TriangleTestJ4.testIsScalene() and

testIsEquilateral() |

// Most of these tests are inspired by the Tutorial 1 quiz

@Test

public void testIsScalene() {

permutedScaleneTest(4, 5, 6, true, "should be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(4, 3, 2, true, "should be scalene!");

// No permutations needed for this one...

scaleneTest(9, 9, 9, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

permutedScaleneTest(4, 4, 2, false, "shouldn't be scalene!");

}

@Test

public void testIsEquilateral() {

Triangle t = new Triangle(4, 5, 6); // Not equilateral

assertFalse(t + " unexpectedly equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

t = new Triangle(1, 1, 1); // Equilateral

assertTrue(t + " unexpectedly not equilateral!", t.isEquilateral());

}

|

Triangle's

constructor. JUnit 4 provides a nice annotation for expected

exceptions, but remember that if a method throws an exception, then no

further code in it will be executed. Consequently, we need to test each

kind of bad triangle in its own individual test:

More tests to add to TrianglTestJ4.java, to see that exceptions are thrown for bad triangles: |

|---|

@Test(expected=st.BadTriangleException.class)

public void testTriangleFirstIsZero() {

new Triangle(0, 1, 1);

}

@Test(expected=st.BadTriangleException.class)

public void testTriangleSecondIsZero() {

new Triangle(1, 0, 1);

}

@Test(expected=st.BadTriangleException.class)

public void testTriangleThirdIsZero() {

new Triangle(1, 1, 0);

}

@Test(expected=st.BadTriangleException.class)

public void testTriangleSidesTooShort() {

new Triangle(1, 1, 2);

}

|

We could also use something like the code at the end of the JUnit 3 version of the first tutorial in

order to “wrap” these tests inside another method, and

execute them more compactly from a single test method (via a

parameter-rotating method, just as we did with permutations for

isScalene()):

| Another way of testing to see that exceptions are thrown: |

|---|

// Make sure that the constructor throws a BadTriangleException

// when given a particular set of parameters.

private void assertConstructorException(int p, int q, int r) {

String m = "Triangle (" + p + ", " + q + ", " + r + ") ";

try {

new Triangle(p, q, r);

fail(m + "didn't throw a BadTriangleException!");

} catch(BadTriangleException e) {

return;

} catch(Throwable t) {

fail(m + "threw a " + t + ", not a BadTriangleException!");

}

}

// This tests all three rotations of p, q, r, to see that each one

// causes an exception.

private void rotatingAssertConstructorException(int p, int q, int r) {

assertConstructorException(p, q, r);

assertConstructorException(q, r, p);

assertConstructorException(r, p, q);

}

// Test constructor to see that bad triangles are rejected.

@Test

public void testTriangle() {

rotatingAssertConstructorException(0, 1, 1);

rotatingAssertConstructorException(-1, 1, 1);

rotatingAssertConstructorException(2, 1, 1);

rotatingAssertConstructorException(3, 1, 1);

}

|

That's it: we've now got a reasonable set of tests for our

constructor, and both isScalene() and

isEquilateral().

Version 1.1, 2010/02/04 14:57:52

|

Informatics Forum, 10 Crichton Street, Edinburgh, EH8 9AB, Scotland, UK

Tel: +44 131 651 5661, Fax: +44 131 651 1426, E-mail: school-office@inf.ed.ac.uk Please contact our webadmin with any comments or corrections. Logging and Cookies Unless explicitly stated otherwise, all material is copyright © The University of Edinburgh |